Stories from the Collection A Half Century in the Making

Scroll to learn more about the

pieces in the Kimbell Collection

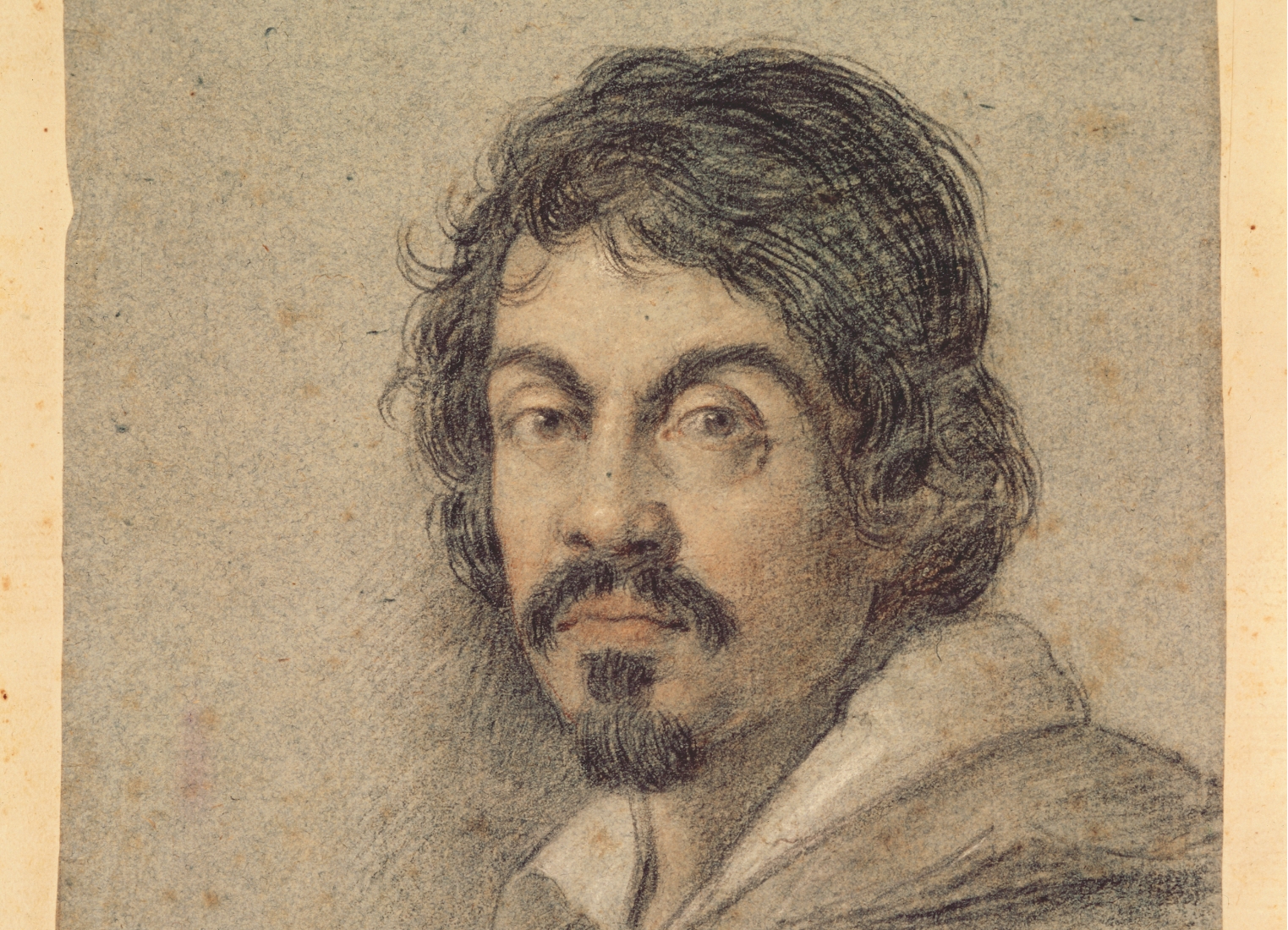

The Cardsharps, c. 1595

Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi), Italian

Key Info

Artist:

Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi) (1571–1610)

Culture:

Italian

Date:

c. 1595

Period:

16th Century

Medium:

Oil on canvas

Year Acquired:

1987

In this picture, two young men stake their luck and wits in a game of cards. A fresh-faced boy dressed in plum-colored velvet studies his hand, unaware of the drama about to unfold.

The viewer, however, is pulled into the action by the painting’s compelling realism and close vantage point. Unlike the young dupe, we see that the rogue standing behind him is signaling his younger accomplice, who prepares to pull out a card hidden in his silken breeches. The younger cheat wears an ostrich-feathered cap and damask doublet with black bands and has a stiletto—a type of dagger—tucked into his belt. This menacing and often outlawed weapon is not the sword of a gentleman. Tap here to view a detail of the dagger.

His attire identifies him as a bravo, or mercenary, like the soldier illustrated in a book of Venetian dress with the observation that bravi “frequently vary their dress, and are always dueling . . . They serve this or that [master] for money, swearing and bullying without provocation, and committing all kind of scandals and murders.” Tap here to view an illustration of a bravo.

The older rogue’s shady appearance and mismatched clothing—which would have been available in the second-hand market—suggest his disreputable character. His gloves exposing fingertips and thumb would have raised suspicion among those wise to the tricks of cardsharps. The game is primero, a forerunner of poker, and cheats marked their cards with needle pricks or raised surfaces that could be felt with the fingertips.

Caravaggio’s Rome attracted not only clerics, pilgrims, and artists, but also beggars, charlatans, and other tricksters, including cardsharps. Caravaggio himself was notorious for criminal behavior—from throwing a plate of artichokes at a waiter and harassing his landlady to homicide. What we know about Caravaggio today comes mainly from court documents. Tap here to view a contemporary drawing of Caravaggio.

For this new type of painting subject, Caravaggio drew inspiration not just from the street and taverns, but from Northern prints, like Hans Holbein’s woodcut depicting gamblers from his Pictures of Death. Tap here to view Holbein’s woodcut of gamblers.

Caravaggio’s cardsharps could also have been plucked from contemporary dramatic performances like the commedia dell’arte, whose stock characters included soldiers of fortune.

The Cardsharps helped to launch Caravaggio’s fast-rising career. His shocking, theatrical style would capture the imagination of many artists working in Rome, who adopted his revolutionary approach and spread it throughout Europe. According to the artist’s early biographer, Giovanni Pietro Bellori, The Cardsharps was purchased by Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte, who gave the young artist an honored place in his household.

The cardinal also purchased Caravaggio’s Gypsy Fortune Teller and other works by the artist, which were stamped on the back with his seal and inventoried after his death. Tap here to view Caravaggio’s Gypsy Fortune Teller.

When the Kimbell Cardsharps was rediscovered in a European private collection in 1987, it was conceivably yet another copy of the lost masterpiece—but its extraordinary quality, along with Cardinal del Monte’s seal on the back of the canvas, removed all doubts. Tap here to view Cardinal del Monte’s seal.

Caravaggio’s Cardsharps inspired countless artists who explored themes of deception and psychological interplay. Among the most memorable is the dazzling Cheat with the Ace of Clubs in the Kimbell collection (and its twin, The Cheat with the Ace of Diamonds in the Musée du Louvre, Paris) by Georges de La Tour. The French artist brings women and wine to the gambling table with his remarkable temptress, who, with a sidelong glance, connives with the maidservant and cheat to swindle the foppish young man. Tap here to view The Cheat with the Ace of Clubs by Georges de La Tour.

Visual Gallery

Swipe to explore images

Still Life with Mackerel, 1787

Anne Vallayer-Coster, French

Key Info

Artist:

Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744–1814)

Culture:

French

Date:

1787

Period:

18th Century

Medium:

Oil on canvas

Year Acquired:

2019

Credit Line:

Gift of Sid R. Bass in honor of Kay and Ben Fortson

Still Life with Mackerel is among the most beautiful works by Anne Vallayer-Coster, the foremost still-life painter in France at the end of the 18th century.

The artist’s magical ability to imitate nature and her skill as a colorist are on display. Cool, silvery tonalities unify the balanced and dynamic composition. The play of light on different materials—from crystal to metal to the mutable skin of the fish—is brilliantly observed.

The mackerel show off Vallayer-Coster’s lively application of paint, rendered with luminous white and gray strokes and dazzling touches of brilliant vermilion and ocher near the gills, indicating the freshness of the fish. Tap here to view the mackerel.

French still lifes with fish are unusual and those with mackerel—a saltwater fish that spoils quickly—virtually nonexistent. Fresh mackerel were, in fact, available in Paris when Vallayer-Coster painted this canvas. They were fished off the coast of Normandy in May and transported by boat or horse to Paris. Most mackerel would have been salted and preserved, but the best mackerel were fresh.

The arrival of rich, delectable mackerel was much anticipated in May: according to the contemporary “Almanach des Gourmands,” people would “gather around them, put them up for auction, and feature them in invitations.” Vallayer-Coster’s still life shows off preparations for this seasonal, springtime mackerel feast. A simple recipe was recommended: stuffed with butter and herbs and grilled or dressed with olive oil and lemon.

The elegant silver cruet set in the latest neoclassical fashion holds thick green olive oil and red vinegar. Vallayer-Coster’s father was a goldsmith—and perhaps this is her own cruet set. Note the reflection of a window at its base! Tap here to view the cruet set.

The silver receptacle was also a luxury item that was used to cool the wine glasses, as its name “rafraîchissoir” or “verrière” suggests. Its lobed edges hold the stems of the glasses, so that the feet protrude. It would have been placed on a side table, with glasses served to each guest. Tap here to view the silver vessel and glasses.

The rich brioche, made with butter and egg, was fitting for a celebration. It also pays homage to Vallayer-Coster’s great predecessor, Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin, who painted this well-known still life featuring a brioche, today in the Louvre. The festive sprig with orange blossoms signals springtime. Tap here to view The Brioche by Chardin.

The plump fish are piled on a freshly pressed white damask cloth. At the corner of the linen at the bottom right, Vallayer-Coster has placed her initials, V and C, and the number 6 below. Such monograms would have been embroidered in tiny red cross-stitch on her very own linens, for her housekeeper’s inventory. Tap here to view the linen cloth with embroidered initials.

In short, this still life whets our appetite for a simple but sumptuous feast, such as would have been enjoyed in well-to-do households like Vallayer-Coster’s own or that of her patrons. It was painted just before the French Revolution, which she survived, despite her bourgeois and aristocratic clientele.

On the strength of her own talents, Vallayer-Coster was by age 26 one of very few women to be accepted as a member of the powerful French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. This allowed her to show her work at the annual Salons and gain critical acclaim and patronage.

At the Kimbell, Vallayer-Coster’s magical still life joins this acclaimed Self-Portrait, painted around 1781 by the great portraitist Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Vallayer-Coster’s slightly younger contemporary, who was also a member of the French Royal Academy. Tap here to view Vigée Le Brun’s Self-Portrait in the Kimbell collection.

Visual Gallery

Swipe to explore images

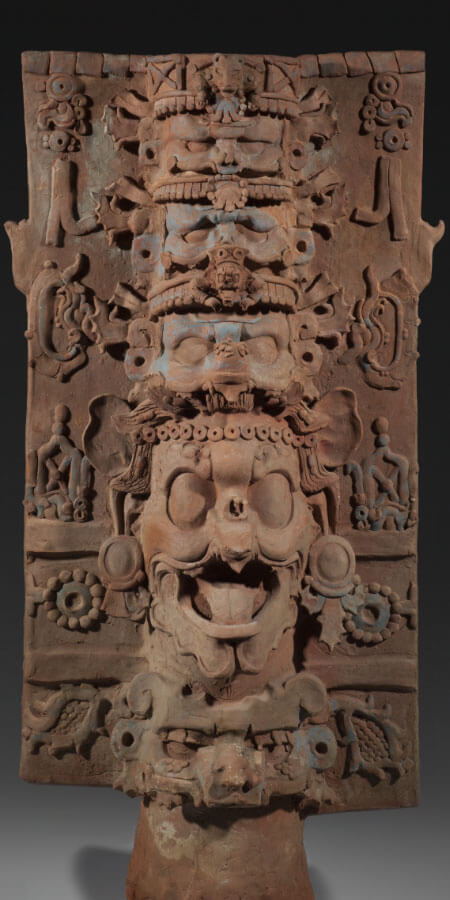

Censer Stand with the Head of the Jaguar God of the Underworld, c. A.D. 690-720

Maya, Late Classic period

Key Info

Culture:

Maya

Date:

c. A.D. 690-720

Period:

Late Classic period

Medium:

Ceramic with traces of pigments

Year Acquired:

2013

This elaborate censer stand, or incensario, played an important role in Maya ceremonial life. Monumental ceramic censer stands are some of the finest and largest freestanding sculptures created by Maya artists. Censers were used in almost all major Maya ritual ceremonies to represent and venerate divine beings.

A brazier-bowl (now missing) was placed on top of the censer stand to burn coals and fragrant copal incense, emitting clouds of smoke to communicate with venerated ancestors and deities in the spiritual realm.

Censers were embellished with a variety of imagery. They most often represented the Jaguar God of the Underworld, as we see in this example now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Tap here to view a censer stand with the Jaguar God.

For the Maya, the center of the universe was the Axis Mundi, or World Tree, which had roots growing deep in the sea under the earth and branches that rose to support the heavens. Symbolically, the tubular bodies of the censer figures formed cosmic trees that made the movement of deities through the cosmos possible during ritual acts.

The Kimbell censer stand is sculpted with a vertical tier of five heads, representing the structure of the Maya underworld, called Xibalba, as it meets the celestial realm. Moving from bottom to top: The lowest head is a version of the Maize God with attached leaves containing corn kernels; he represents the Underworld, as maize grows from under the earth. Tap here to view the Maize God at the bottom of the censer stand. Above the Maize God’s head is the principal head of the Jaguar God of the Underworld, who represents the sun at night during its Underworld journey from dusk to dawn. Tap here to view the head of the Jaguar God. The Jaguar God head is capped by Itzamye, the serpent-bird that was killed in the branches of the World Tree just prior to the creation of the present world. The shift from the Jaguar God of the Underworld to Itzamye symbolizes the surface of the earth and the interface between the Underworld and the celestial realm. In the headdress of Itzamye is a small figure that may be a version of the Jester God, a signifier of rulership. Tap here to view Itzamye in detail. The head above Itzamye has not been identified.

At the apex is the head of Itzamna, the paramount sky god of the Maya, who resided at the top of the heavens. A small jaguar is perched in Itzamna’s headdress. Note the traces of original blue, red, and white pigments on the surface of this well-preserved censer stand. Tap here to view the head of Itzamna.

This censer is one of a pair in the Kimbell collection. The two censers likely adorned the entrance or staircase of a Maya ceremonial building. Tap here to view the Kimbell’s Censer Stand with the Head of a Supernatural Being. The sophistication and superior craftsmanship of this pair of censer stands suggest they are from Palenque, an important Maya city-state located in the current-day state of Chiapas, Mexico, that flourished in the seventh century. Tap here to view a photograph of the site of Palenque.

Visual Gallery

Swipe to explore images

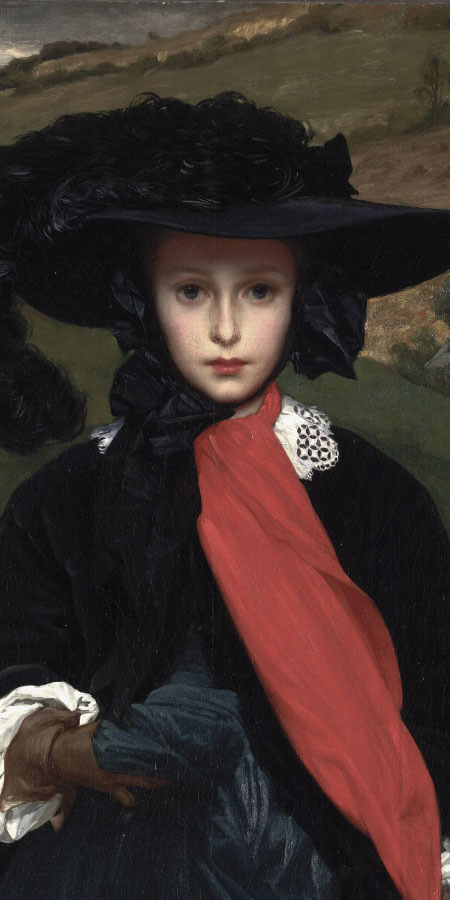

Portrait of May Sartoris, c. 1860

Frederic Leighton, British

Key Info

Artist:

Frederic Leighton (1830–1896)

Culture:

British

Date:

c. 1860

Period:

19th Century

Medium:

Oil on canvas

Year Acquired:

1964

Her dark, wide eyes shaded by a large-brimmed hat, a young woman walks toward us in this captivating full-length portrait, seemingly lost in thought.

The work depicts Mary Theodosia (called May) Sartoris when she was about fifteen years old. It was painted by Frederic Leighton, a friend of May’s mother. Although British, Leighton lived abroad as a youth and trained in the continental academic tradition in Germany, Italy, and France. He was a leading artist of the tendency in British art concerned with beauty and form, known as the Aesthetic Movement.

May’s mother, Adelaide Kemble Sartoris, was a member of the Kemble family—a distinguished English theatrical dynasty that included her aunt, the celebrated actress Sarah Siddons. Acclaimed as one of the finest singers in England, Adelaide had a successful opera career—as we see in this 1841 print showing her in the role of Norma. Tap here to view Adelaide Kemble as Norma.

However, she left the stage to marry a wealthy Anglo-Italian, Edward Sartoris, living between England, France, and Italy. She flourished as the hostess of an artistic salon in Rome, whose circle included the poets Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning—and the young Leighton.

This photograph of Adelaide was taken in 1860. Tap here to view a photograph of Adelaide Sartoris. Leighton painted May’s portrait around that time, the year after he settled in London, coinciding with the Sartorises’ move back to England. May is probably depicted in the setting of the family’s country residence in Hampshire. She wears a fashionable riding habit with a voluminous skirt, jacket, white embroidered collar, and ”pagoda” sleeves. Tap here to view a fashion plate of a riding habit.

The feathered hat and the dashing, long, vivid red scarf befit a member of the theatrical Kemble family. But the oversized clothing also calls attention to her age and fragile beauty, and to her transition from childhood to adulthood. The fallen tree behind her, too, suggests the passage of time and mortality.

In fact, unlike her mother—who regretted leaving the stage—May was content as an amateur actor and singer. She married Henry Evans Gordon in 1871, and the couple had four daughters. Leighton painted this intimate portrait of May wearing a veil, possibly as a wedding present. Tap here to view Portrait of May Sartoris, c. 1871, by Frederic Leighton.

Settling into a fashionable studio house in London, Frederic Leighton, too, enjoyed a successful career. He was elected president of the Royal Academy in 1878 and elevated to the peerage in 1896.

Portrait of May Sartoris was purchased by Mr. Kay Kimbell in 1964, shortly before his death and before the Kimbell Art Museum opened in 1972. He had long expressed a desire to purchase a “Pinkie”—that is, Thomas Lawrence’s 1794 portrait of Sarah Goodin Barret Moulton, whose ethereal magic had captivated him in the collection of the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California. Tap here to view “Pinkie” by Thomas Lawrence.

Portrait of May Sartoris offers a very different, and distinctly Victorian, view of childhood in a beguiling picture that has remained a favorite among the Kimbell’s collection.

Visual Gallery

Swipe to explore images

Chibinda Ilunga, Mid-19th century

Chokwe, Angola

Key Info

Culture:

Chokwe

Date:

Mid-19th century

Period:

Mid-19th century

Medium:

Wood, hair, and hide

Year Acquired:

1978

This sculpture represents Chibinda Ilunga, the royal ancestor of the Chokwe people who lived in a forested area populated with elephants in present-day Angola in Western Africa.

Chibinda Ilunga was a legendary culture hero who introduced the Chokwe people to refined social manners and advanced hunting techniques, critical for their survival. We can identify this sculpture as Chibinda Ilunga by the way he is portrayed and by the various items of dress and implements he carries—and also by the very skillful way the figure is carved by a professional, master artist who was entrusted with depicting the divine king.

A close look at the sculpture reveals its assets. The elaborate headgear with rolled side elements is a sign of Chibinda Ilunga’s royal rank. Tap here to view headgear.

The staff in his right hand represents his leadership and supports the hunter on long journeys, while the antelope horn in his left hand holds protective medicines. Tap here to view antelope horn.

Made of real hair, Chibinda Ilunga’s long beard indicates aristocratic stature and wise nature. His broad forehead and wide eyes show the intelligence of the enlightened ruler. Tap here to view Chibinda Ilunga’s head.

The graceful and meticulous carving expresses the hero’s superior qualities. The sculpture’s broad shoulders and flexed, muscular legs suggest incipient movement and the stealth of the hunter. Tap here for a side view of Chibinda Ilunga. Chibinda Ilunga’s large hands and feet also indicate power and dynamic physical strength. Even details such as toenails and fingernails are carefully described.

The Chokwe people used specific terms to praise the beauty of this sculpture: utotombo—to describe its skillful, careful execution—and cibema—a word that means, in English, both “beautiful” and “good.” In other words, the sculpture’s physical beauty is matched by its moral virtue.

Chibinda Ilunga was a role model for Chokwe chiefs. Such sculptures would have been part of an altar and served to fight off physical as well as metaphysical threats. Pictured is another impressive sculpture that represents the culture hero. Tap here to view Chibinda Ilunga, Museum Rietberg, Zurich.

Fewer than twenty mid-nineteenth-century representations of Chibinda Ilunga have survived. Many consider the Kimbell example to be the finest.

Visual Gallery

Swipe to explore images

Court Lady, first half of the 8th century A.D.

Chinese, Tang dynasty

Key Info

Culture:

Chinese

Date:

First half of the 8th century A.D.

Period:

Tang dynasty (A.D. 618-907)

Medium:

Gray earthenware with painted polychrome

Year Acquired:

2001

This charming Court Lady stands just over 16 inches tall in a gracefully swayed pose, her petite hands held in a conversational gesture in front of her swelling form.

Made some 1300 years ago, the well-preserved earthenware figure was placed in a tomb during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD)—a period of great prosperity and cultural productivity. This was the time of the great Silk Road, when trade of exotic goods from foreign lands stretched all the way to the Western world and encouraged cultural exchange in China.

Burial rituals at this time reflect the belief that a person had two souls with different functions in death: one stayed on earth with the body while the other traveled to a Daoist paradise. Funerary provisions, including effigy sculptures like this one, created a comfortable tomb for the soul’s eternal rest on earth. Tang funerary sculptures included warriors, animals, sports players, musicians, and other companions that might have accompanied the deceased in life. Fierce guardians that warded off intruders, such as this Earth Spirit in the Kimbell collection, took the form of hybrid creatures. Tap here to view the Kimbell Tang Earth Spirit.

However, representations of court ladies are among the most engaging groups of funerary figures. The Tang sculptors’ careful attention to details of fashion and physiognomy allow us to trace changing fashion and beauty standards of ladies at court during this period.

In the early eighth century, a new aesthetic favored a fuller physique and loose billowing robes, like those seen here. This fashion was probably set by Yang Guifei, the imperial consort of the emperor Xuanzong (reigned A.D. 712–56), who was known to be a woman of more ample proportions. The Kimbell’s Court Lady wears a white long-sleeved jacket tucked into a full-length red robe that falls in looping folds at her feet, where her upturned, ruyi-shaped, triple-cloud shoes peek out. Tap here to view the Court Lady’s shoes.

Some of these ancient shoes have survived, like this lovely example. Tap here to view a photograph of Tang-period shoes.

The Kimbell figure’s plump, heavily made-up cheeks are offset by exquisitely delicate eyes, nose, and slightly parted lips. Tap here to view the figure’s face in detail.

Her fashionable hairstyle, known as a gaoji (upswept topknot), is stiffly lacquered and folded, with a clump of hair separated and bound into a fan shape in the front, all held in place by two crescent-shaped combs. Tap here to view coiffure with combs.

A fabled story relates that one day Yang Guifei, an accomplished horsewoman, fell from her horse while riding but picked herself up and pushed her elaborate coiffure back into place. Consequently, the hairstyle seen here is described as “falling off horse” hair!

Visual Gallery

Swipe to explore images

Standing Shaka Buddha, c. 1210

Kaikei, Japanese

Key Info

Artist:

Kaikei (active c. 1185–1225)

Culture:

Japanese

Date:

c. 1210

Period:

Kamakura

Medium:

Gilt and lacquered wood

Year Acquired:

1984

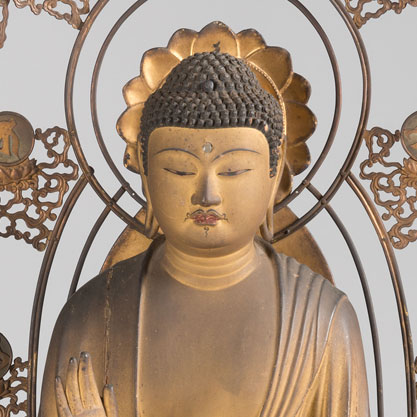

This rare image of the historical Buddha, Shaka (Shakyamuni), was made by Kaikei, the great master sculptor of the Kamakura period (1185–1333), who established the primary school of sculpture that produced statuary for the major temples in Nara and Kyoto in Japan.

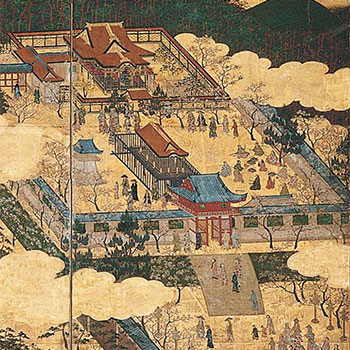

It would have been displayed in a temple, such as those depicted in this Japanese screen in the Kimbell collection. Tap here to view the screen.

The figure is identified as the historical Buddha, Shaka (Shakyamuni), by the gesture of reassurance (abhayamudra) of the right hand.

In 2017 the Kimbell sculpture traveled to Japan to be featured in the exhibition The Buddhist Master Sculptor Kaikei: Timeless Beauty from the Kamakura Period, held at the Nara National Museum. Conservators and curators studied the remarkably well-preserved one-thousand-year-old figure. Tap here to view publicity for the Kaikei exhibition in Nara.

CT scanning revealed intriguing details about how the wooden sculpture was constructed. The interior cavity in the head, neck, and body—which would never have been seen—is completely smooth, indicating the care and expense that went into its creation. The scan also confirmed that there are no prior restorations. Even the nails are ancient. Tap here to view Standing Shaka Buddha and CT machine.

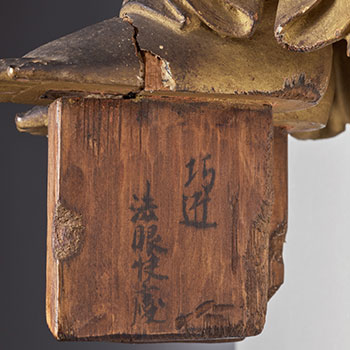

The sculpture is signed on the tendon of the foot inserted into the lotus base. The inscription reads: “Kōshō hōgen Kaikei.” “Kōsho” means “highly skilled craftsman” and “hōgen” means “Eye of the Law,” an ecclesiastical rank awarded to sculptors. Tap here to view the inscription.

Kaikei’s distinctive style is refined and graceful. With left foot advancing, the Buddha appears to move forward to greet the devotee with an expression of gentle and profound compassion. The master’s style is notable for the beautiful proportions of the figure and the way that the elegant robe that covers the body falls in rhythmical folds, rippling across the stomach and cascading over the arms. Tap here to view the folds of the sleeve.

The figure is entirely covered with gold lacquer. The robe is further embellished with an exquisite floral and geometric pattern of fine-cut gold leaf, a technique known as kirikane, which is laid over the gilded surface, giving the sculpture a greater sense of realism. Tap here to view kirikane gold leaf.

Among the thirty-eight verifiable attributions to Kaikei, the Kimbell’s sculpture is the only known image of Shaka Buddha. The curator of the exhibition in Japan declared the Shaka Buddha in the Kimbell collection to be “the best sculpture by Kaikei.”

Visual Gallery

Swipe to explore images

Modello for the Triton Fountain, Piazza Navona, Rome, 1653

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Italian

Key Info

Artist:

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680)

Culture:

Italian

Date:

1653

Period:

17th Century

Medium:

Terracotta

Year Acquired:

2003

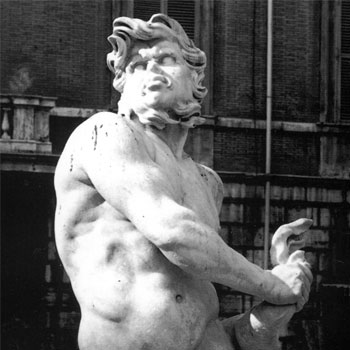

This dynamic figure is the largest known terracotta sculpture by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the greatest sculptor of the Roman Baroque. In 1651, Bernini received orders from Pope Innocent X to renovate the fountain at the southern end of Piazza Navona in Rome—just opposite the pope’s immense family palace.

At the center of the elongated piazza, Bernini had just completed the spectacular Fountain of the Four Rivers (1648–51), also a commission of Pope Innocent X. Bernini’s earliest designs for the southern fountain were small in scale. He created this magnificent terracotta as a presentation model to win the pope’s approval for the final statue. Its twisting pose beckons visitors from wherever they enter the piazza to admire Bernini’s virtuoso rendering of the figure’s anatomy, a skill honed from his study of ancient Roman statues and the live model. Bernini referred to the figure as Triton, a mythological sea deity.

In his design for the fountain, the sculptor placed Triton on a giant conch shell that he rides like a wave as he grapples a fish from whose mouth the fountain’s water would flow. Tap here to view a detail with the fish and conch.

Bernini’s terracotta modello also likely guided the carving of the final statue in marble, which was delegated to an assistant, Giovanni Antonio Mari. In the marble, we can visualize a few parts, including an arm, that have been damaged in the fragile clay modello. Tap here to view the over-lifesize Triton in Piazza Navona.

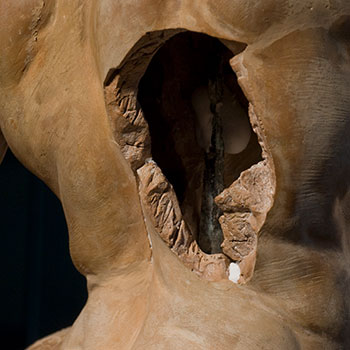

After its acquisition by the Kimbell, conservator Tony Sigel, an expert on Bernini’s clay modeling techniques, conducted extensive technical study and conservation of the terracotta. Tap here to view a photograph of Tony Sigel at work.

Sigel employed X-radiograph technology to view earlier repairs and to analyze the work’s structure. To minimize shrinking and cracking of the clay during firing, Bernini had hollowed out the head and the torso, accessed through a hole on the back of the shoulder. To stabilize the sculpture, Sigel needed to take it apart. He devised a miniature crane to help with the process. Tap here to view Sigel at work with an improvised crane.

Tap here to view the Triton’s torso during restoration.

With the statue partially disassembled, Sigel could more easily address early repairs to the legs, shell, and base of the Triton. Some of these had resulted in serious misalignments. The Triton’s right foot, for example, had become detached and improperly reconnected. Sigel put the foot back as Bernini intended, with its heel slightly lifted—a subtle but important design feature. He worked carefully with colored fill materials to hide the earlier breaks. Tap here to view photographs of the foot before and after restoration.

A section of rocks on the base that had been lost and poorly restored was removed, and a new area of rocks was created in painted plaster. Tap here to view the rock base before and after restoration. For the textures, Sigel reconstructed Bernini’s modeling tools by taking molds of the various parallel striations left on the authentic parts of the rockery. He used these patterns to create clawed heads identical to Bernini’s tools. Tap here to view Sigel adding texture to the base.

Sigel’s painstaking methods ensured that this new rockery blends seamlessly with the rest of the base. The restored terracotta statue is now free of disfiguring repairs so that we can enjoy Bernini’s prodigious talent in modeling this lively figure.

Visual Gallery

Swipe to explore images

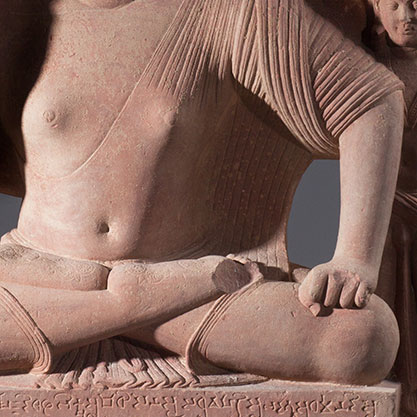

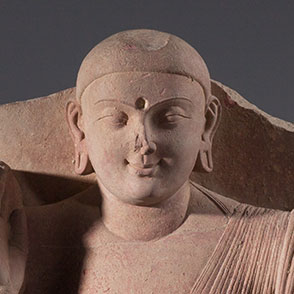

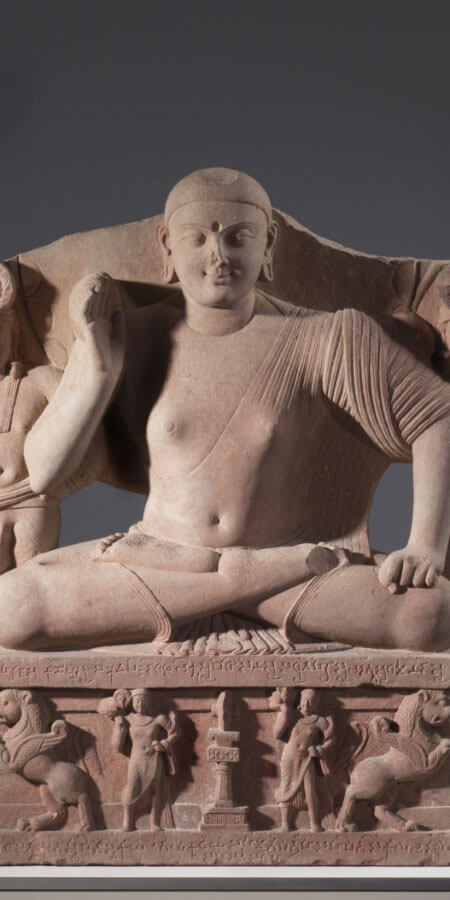

Seated Buddha with Two Attendants, c. A.D. 131

Indian, Kushan period

Key Info

Culture:

Indian

Date:

c. A.D. 131

Period:

Kushan Period

Medium:

Red Sandstone

Year Acquired:

1986

This rare sculpture of Seated Buddha with Two Attendants is one of the earliest surviving figures of the Buddha represented in human form. Prior to the first century A.D., the Buddha was represented in art only in symbols such as a wheel, a footprint, a stupa, or a Bodhi tree.

Tap here to view Footprints of the Buddha, Yale University Art Gallery.

The well-preserved early figure in the Kimbell collection portrays the Buddha as Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha and teacher. He is seated as a traditional yogi and dressed in a monastic garment draped over the left shoulder.

The sculpture exemplifies the distinctive style of works produced in the city of Mathura in present-day Uttar Pradesh. Mathura was the second capital of the Kushans, who ruled much of northwestern India and the ancient region of Gandhara (parts of present-day Pakistan, and Afghanistan) from the first to the third century AD. Mathura was not only a politically and economically significant site but also an important center for artistic production.

The mottled red sandstone is one indication that Seated Buddha with Two Attendants was carved in Mathura, where sculpture developed out of indigenous traditions and made use of local materials. Tap here to view the red sandstone material.

Typical of the Mathura style, the artist has given special attention to modeling the figure’s body. Tap here to view the upper half of the Buddha.

The sensitive carving of Buddha’s plump flesh and sturdy form, revealed through the clinging garment, gives the figure a commanding and dignified presence. His chest swells as if he has just taken a deep breath, called prana, as one does in yoga. The Buddha’s face is calm and impassive, except for a subdued smile. The two attendants mirror the Buddha’s expression.

Seated Buddha with Two Attendants and other early sculptures of the Buddha adopt several common features to represent the spirituality of the Buddha:

The halo (partially lost) symbolizes the sun and Buddha’s divinity. Tap here to view the head of the Buddha. The cranial bump (ushnisha), now lost, represents Buddha’s great wisdom. The elongated ears, stretched from the heavy earrings the Buddha wore as a prince, denote the material world he renounced. The dot between his eyes (urna), which may have held a rock crystal, symbolizes spiritual knowledge.

The gesture of reassurance of the raised right hand is called abhayamudra and represents the Buddha’s compassion and his role in teaching the path towards Enlightenment. Tap here to view the Buddha’s right arm.

Two sensuously modeled royal attendants flank the Buddha; their small size and rich dress contrast with the larger scale and simple dress of the Buddha, amplifying his significance as a universal monarch. The lotus and wheel marks on the Buddha’s hands and feet denote his divinity and teaching.

The relief panel of the throne also contains a pillar topped by a wheel that symbolizes the Buddha’s preaching—his first sermon at Sarnath when he put “the wheel of the law” into motion—and is flanked by two lions and two figures holding flywhisks, to signify Buddha’s royal heritage. Tap here to view the lower half of sculpture with relief panel.

At the base of the throne, there is a carved dedicatory inscription in Sanskrit which names the donors and gives a date corresponding to the fourth year of the reign of the Kushan ruler (Kanishka I), likely c. A.D. 131.

Visual Gallery

Swipe to explore images

The Torment of Saint Anthony, 1487

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Italian

Key Info

Artist:

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564)

Culture:

Italian

Date:

1487

Period:

15th Century

Medium:

Tempera on panel

Year Acquired:

2009

This is the first known painting by Michelangelo, believed to have been painted when he was twelve years old.

Writing when Michelangelo was still alive, his earliest biographers, Giorgio Vasari and Ascanio Condivi, tell us that, aside from some drawings, his first work was a painted copy of the engraving Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons by the fifteenth-century German master Martin Schongauer.

Although Michelangelo considered himself first and foremost a sculptor, he received early training as a painter in the workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio (c. 1449–1494). Such prints would have been available in the studio of the Florentine master, and Michelangelo reportedly made his copy under the guidance of an older friend, the artist Francesco Granacci. Tap here to view Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons by the fifteenth-century German master Martin Schongauer.

The rare subject from the legend of Saint Anthony the Great recounts how the Egyptian hermit-saint experienced a vision in which he levitated into the air and was attacked by demons. Implacable, he withstood their torments. In comparison with Schongauer’s print, it is instructive to review Michelangelo’s subtle revisions to the German master’s composition. Overall, he made it more believable and compact, enlivening it with color and adding a landscape that resembles the Arno River Valley around Florence. Tap here to view the landscape.

Vasari tells that to create the strange forms of the devils, Michelangelo bought fish with bizarrely colorful scales. Condivi wrote that in order to give these creatures veracity, Michelangelo went to the fish market to study the shape and color of the fins, eyes, and other parts of the fish. Michelangelo’s rendering of the spiny long-snouted demon with brilliantly colored scales—absent from the engraving—particularly chimes with these descriptions. Tap here to view the spiny long-snouted demon. He also scraped away paint along the back of this monster to enhance the sculptural form of the thick scales, which are painted in relief.

Michelangelo made thoughtful, calibrated adjustments to shift the placement of figures. He straightened the tilt of Saint Anthony’s head and altered his expression, adding a halo. Tap here to view the head of Saint Anthony.

The artist reframed the heads of the demons by refining the space around them, emphasizing their fantastic features. For example, Michelangelo moved the horns of the long-necked demon in the lower left so that the demon below could bite one of them. Tap here to compare the heads of Michelangelo’s and Schongauer’s monsters.

Recently, advanced imaging technology revealed that a quick compositional sketch of a fresco in the Tornabuoni Chapel of Santa Maria Novella was made underneath the paint layers of the rocks in the lower part of the panel.

This scene was painted before October 1487—thus confirming that Michelangelo painted The Torment of Saint Anthony while he was informally associated with Ghirlandaio’s workshop and before he joined as an apprentice in April 1488. One of only four easel paintings generally regarded as having come from his hand, The Torment of Saint Anthony is the first painting by Michelangelo to enter an American collection.

Visual Gallery

Swipe to explore images

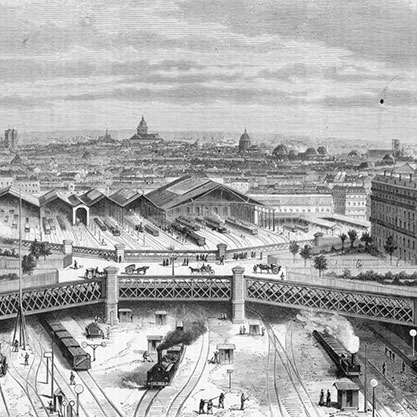

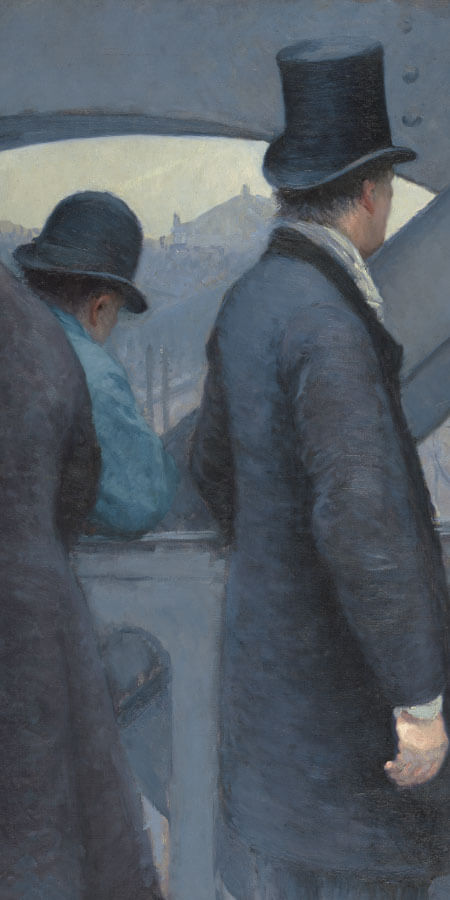

On the Pont de l’Europe, 1876-77

Gustave Caillebotte, French

Key Info

Artist:

Gustave Caillebotte (1848–1894)

Culture:

French

Date:

1876-77

Period:

19th Century

Medium:

Oil on canvas

Year Acquired:

1982

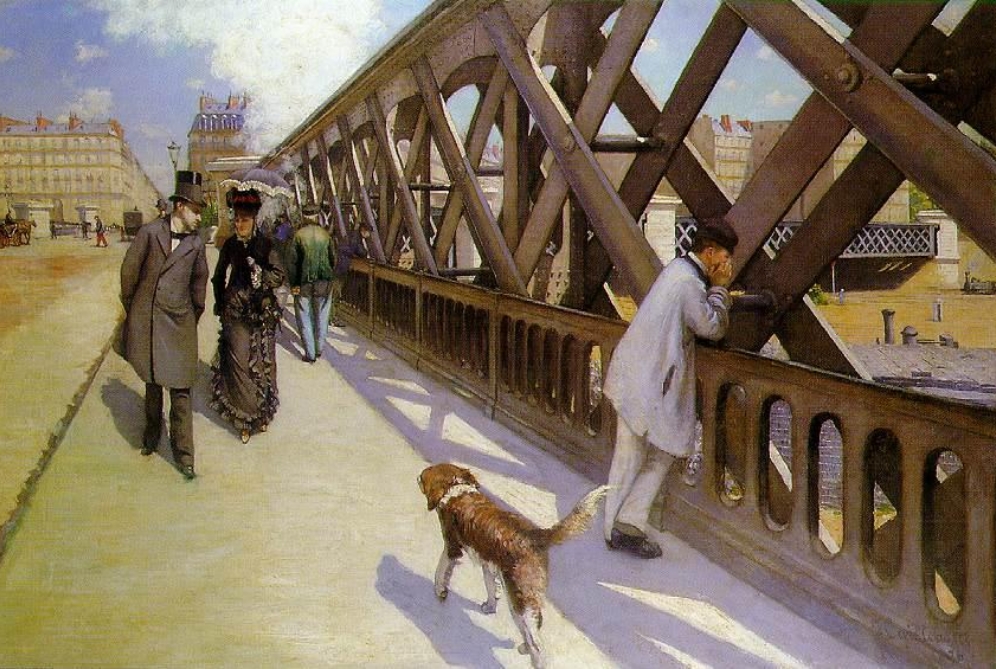

On the Pont de l’Europe is one of a series of paintings whose subject was the new urban spaces of Paris that Gustave Caillebotte painted in the years around 1875. A vast rebuilding campaign was transforming the city, as crowded medieval quarters were demolished and replaced with broad avenues that facilitated easy movement to the trains, suburbs, and the world beyond.

This campaign of renewal and industrialization changed the urban landscape—at once thrilling and unsettling to the citizens of Paris for its upheaval of everyday life.

Several of Caillebotte’s paintings from this series—including his famous Paris Street, Rainy Day (Art Institute of Chicago) were on view at the Kimbell’s 2015–16 exhibition, Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye, as we see in this installation view. Tap here to view Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye, exhibition photo.

The mammoth, star-shaped bridge, the Pont de l’Europe, was built in the 1860s to bring travelers to Paris’s principal train station, the Gare Saint-Lazare, which was expanding to meet demand. This illustration, contemporary with Caillebotte’s painting, shows how the new bridge connected six broad avenues, spanning the vast railyard below. Tap here to view an 1868 print of the Pont de l’Europe. The Pont de l’Europe was a popular place to promenade, and Parisians of all classes found themselves sharing a new type of urban space.

Caillebotte lived nearby, and his fellow impressionists Edouard Manet and Claude Monet had studios in the area. Born into a well-to-do Parisian family, Caillebotte—whom we see in this photograph taken by his brother, an amateur photographer— became a patron and advocate of the impressionists, whose work he collected. Tap here to view the photograph of Caillebotte. Donated to the French state after his death, those paintings are now in the Musée d’Orsay, Paris. The impressionists aimed to paint modern life in a modern and authentic way. As the writer Émile Zola declared: “Our artists have to find the poetry in train stations, the way their fathers found the poetry in forests and rivers.”

Caillebotte’s earlier version of Le Pont de l’Europe (now in the Petit Palais, Geneva) shows Parisians of various social classes strolling on the sun-drenched bridge. Tap here to view Caillebotte’s earlier painting, Le Pont de l’Europe.

But instead of the sweeping perspective of the Geneva painting—which was inspired by the optical effects of photography and by the compositions of Japanese ukiyo-e prints—Caillebotte has created an even more radical composition. Huge iron girders of iron crisscrossing the flattened composition, along with the openings in the cast-metal balustrade, offer fragmented glimpses of the station roof at right and the rooftop of the newly opened Opera to the left. The figures—the central man in a top hat, the man in a blue worker’s smock leaning on the balustrade, and a third exiting at left—are not engaged with each other but seem isolated, despite their proximity. The pervasive cold gray-blue palette reinforces the sensation of a bracing morning chill. Caillebotte’s melancholy painting conveys the conflicted feelings provoked by the new urban landscape—in a manner very different from the misty pictorial effects of Monet, who in 1877 painted a series of canvases of Gare Saint-Lazare that captured the station enveloped in manmade steam and smoke. Tap here to view one of Monet’s paintings of Gare Saint-Lazare.

Visual Gallery

Swipe to explore images

Equestrian Portrait of the Duke of Buckingham, 1625

Peter Paul Rubens, Flemish

Key Info

Artist:

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

Culture:

Flemish

Date:

1625

Period:

17th Century

Medium:

Oil on Panel

Year Acquired:

1976

The celebrated Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens was not only a painter but also a diplomat who could be entrusted with sensitive negotiations among royalty, noblemen, and high-ranking statesmen.

His ability to create public images to elevate his patrons’ stature was unrivaled. The subject of the Kimbell painting is George Villiers, the first Duke of Buckingham and favorite of King Charles I of England.

In 1625, Rubens went to Paris to install the magnificent cycle of paintings depicting the life of Marie de’ Medici in the Palace of Luxembourg. Tap here to view Rubens’s Marie de’ Medici cycle.

That same year, Marie de’ Medici’s daughter, Henrietta Maria, who was the sister of King Louis XIII of France, was to be married by proxy to King Charles I. This strategic marriage had been negotiated by the Duke of Buckingham. During his visit to Paris, the duke commissioned a grand equestrian portrait of himself from Rubens. This lively drawing of Buckingham’s head must have been sketched from life during their meeting in Paris so Rubens could capture his features. Tap here to view the drawing.

As part of his preparatory process, Rubens also painted oil sketches for his compositions. The Kimbell panel is the sketch for the oversized equestrian portrait. Rubens depicts Buckingham in all his glory, with signs of his high stature and military rank. In the portrait, Rubens captures the charisma of Buckingham, who was also admired for his athleticism as a dancer, rider, and fencer. A contemporary observed: “he was the handsomest bodied man in England.”

In his youth, Villiers entered the service of Charles I’s father, King James I. His rise was meteoric—from cupbearer (1614) to Gentleman of the Bedchamber (1615) to Master of the Horse (1616) in charge of the King’s stables—a very prestigious position at court. Villiers was named a knight of the elite Order of the Garter, whose blue sash and medal he wears in this sketch. In 1619, he was made Lord High Admiral of the Navy. The sea god Neptune and a naiad who is adorned with pearls, pictured at lower left, suggest his dominion over the sea. Tap here to view Neptune and a naiad.

Moreover, Villiers quickly rose from earl to marquess and then to Duke of Buckingham—the only duke outside the royal family—in 1623. His red cape fluttering, he wears light armor and lifts his baton, as his horse rears on command. To magnify the duke’s glory, overhead Rubens depicts the winged figure of Fame with a trumpet in hand, crowning the duke with laurel and declaring victory. Tap here to view Fame.

As we see in the Kimbell picture, Rubens reinvigorated the equestrian portrait to create a dramatic, iconic type that demonstrated the glory and power of military leaders and rulers who expertly control their steeds. Jacques-Louis David’s famous portrait of Napoleon Leading His Army over the Alps follows Rubens’s example. Tap here to view David’s painting of Napoleon.

The monumental equestrian portrait for which the Kimbell oil sketch is preparatory, executed with the help of Rubens’s studio assistants, must have pleased the Duke’s vainglory. However, it was destroyed by fire in 1949. Tap here to view Rubens’s full-scale equestrian portrait of the Duke of Buckingham.

And despite the confidence and bravura that Rubens captures in his portrait of Buckingham, his rise to fame was stopped short. Privately, Rubens had noted Buckingham’s “arrogance and caprice” and predicted that he was “heading for the precipice.” History proved him correct. The duke’s disastrous military campaigns against Spain and France were highly resented. In 1628 he was assassinated, as dramatized in this later print. Tap here to view the print showing the assassination.

Visual Gallery

Swipe to explore images